Il Mondo/Le Monde/The World

Through the centuries, this card has had only one name: The World. Unravelling this card’s meaning won’t be a simple task. In fifteenth-century Italy, the World card wasn’t always at the end the trump sequence, and it didn’t look like the World card we’re accustomed to. In some decks, these two cards depict the Last Judgment and arrival in Paradise. But there may be other stories hidden in these cards that we can decode with the help of similar imagery in medieval and renaissance art.

Fifteenth Century World Cards

World Card as Paradise

All 15th century Italian World cards display a landscape enclosed in a circle. After the resurrection and implied judgment in the previous card, we arrive in Paradise, a renewed and transfigured cosmos. In the geocentric model of the universe, the earth is the center of the cosmos surrounded by concentric rings of elements, planets, and ranks of angels. The center of this geo-cosmic diagram contains a landscape similar to the Budapest tarot card to the left.

The Bible and Petrarch provide two important templates for this version of the World card.

Petrarch and the Triumph of Eternity

Petrarch’s poem I Trionfi provided the archetype for all triumphal processions, whether they were actual parades, painted allegories, or tarot trumps. Each section of the poem describes an allegorical figure that triumphs over the previous one. “Eternity” is the final figure that triumphs over all. This is how Petrarch describes the eternal, transformed universe: “…I at last beheld a world made new and changeless and eternal. I saw the sun, the heavens, and the stars and land and sea unmade, and made again more beauteous and more joyous than before.”

This illustration of Petrarch’s Triumph of Eternity depicts a cosmological diagram like the ones in the previous paragraph, with God and his angels sitting on the rim presiding over the renewed world. In 15th-century tarot decks, we usually see an allegory of Fame standing on the rim of the circle, while the angels with trumpets shift to the Judgment card.

World Card as the New Jerusalem

In the book of Revelation, after twenty chapters of death, plague, misery, and the destruction of the city of Jerusalem and its temple, God returns to preside over a renewed world where there is no death, pain or sorrow. Revelation Chapter 21 begins, “And I saw a new heaven and a new earth: for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away; and there was no more sea. And I, John, saw the holy city, New Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband. “

Verses 12 through 25 describe the New Jerusalem. It has high walls laid out in a square with twelve gates made of pearl guarded by twelve angels. The walls are made of jasper, and the city is pure gold with streets paved with gold. The foundations contain twelve different precious gems. There is no sun or moon because the city is lit by the glory of God; and there is no temple because the Lamb of God is the temple. This manuscript illustration, with a walled city and a lamb in the center, adheres aproximately to the biblical description, and differs considerably from the tarot rendition of the transformed world.

The Visconti-Sforza World card is often seen as a New Jerusalem. But it doesn’t follow the description in Revelation, as it has only one gate, there is no lamb in the center, and there is a temple in the background. A walled city similar to the Visconti-Sforza World card appears in the Tarot de Marseille pattern on the Ace of Cups.

The story depicted in fifteenth-century tarot decks may not always be a simple ascension to paradise. In the earliest decks from Florence and Bologna, the Judgment card was topmost and the World card preceded it. This tells a very a different story—the allegory of Fame presiding over the physical universe followed by the final judgment representing Eternity.

World Card as Fame

In these two Bolognese cards, we see the same geocentric cosmos as in the cards above: a hilly landscape with buildings inside a circle. In the Rosenwald card (left) an angel holds an emperor’s sword and globe, and stands on a laurel wreath. All these symbols point to worldly power and dominance. In the Bolognese tradition (right) Mercury stands on a symbol of the world holding his caduceus and the globus cruciger of worldly power. Both cards are from decks where the Judgment card comes last after the if World. This type of World card, coming before Judgment, illustrates Petrarch’s thesis that if you climb to the pinnacle of worldly success, your fame and reputation will allow you to transcend death, at least until Eternity has the final word.

World Card as Anima Mundi

The World card that was imported to France shortly after 1500 has a nearly naked figure wreathed a mandorla, or vesica pisces. In Christian art, the mandorla signifies the presence of the transcendent, a miraculous act that occurs beyond time and space. Shown here are two common uses of the mandorla in European art: enclosing Christ in glory ruling the world, and the bodily assumption of the Virgin Mary into heaven.

The four creatures accompanying Christ in glory are an artistic convention dating from the early Middle Ages. They first appear in Ezekiel’s vision in the Old Testament (Ezekiel 1:5-10). In the second century, a Greek Bishop, St. Irenaeus, associated the four beasts with the four evangelists: Matthew with the man, John with the lion, Luke with an ox and Mark with an eagle. Two centuries later, the Cypriot bishop Epiphanius proposed switching John and Mark, an association currently in use.

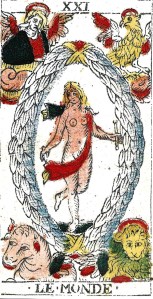

The figure on the earliest Tarot de Marseille World cards may be male, and could possibly be Christ in glory surrounded by the four evangelists. In the Vievil card (left) from the mid-17th century, the figure is naked except for a cloak and the well-placed staff telling us this is a male figure. His halo indicates he may be Christ. The card on the right is an example of the earliest Type I Tarot de Marseille deck. The card was printed in the mid-18th century by Jean Payen of Avignon from a wood block that had been carved a century earlier. By this time, Type I cards had become standardized to show an ambiguous figure with long hair wearing a belt of leaves and holding a short wand.

By the late 17th century, an alternate Tarot de Marseille, known as Type II, had emerged. The central figure, who is obviously female, wears a red scarf draped diagonally across her body, and holds two small wands. She appears to be dancing, and her legs may have been deliberately placed in the same position as the Hanged Man’s legs.

The Type II World card retains the mandorla and the four evangelists of Christian art, but the central figure became associated with the Anima Mundi, the World Soul, the vital force that permeates all of creation. This force moves the stars and planets in their orbits, makes plants grow, gives animals consciousness, and gives humans their reason. This concept originated in ancient Greece, and it’s popularity waxed and waned over the centuries in Christian Europe. The Anima Mundi reached its peak of popularity with the revival of Platonic philosophy in the Renaissance. For Christians, the Anima Mundi is a power under God’s control. Alchemists see it as the fire that facilitates change and transformation.

The Occult World Card

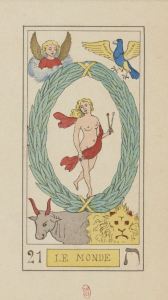

French and British occultists adhered closely to the Tarot de Marseille design, seeing the dancer as a goddess in perpetual motion, generating the energy that fuels the cosmos. This card signifies the culmination of personal evolution, when one sees all reality in a spiritual light.

Oswald Wirth (left) made minor changes to the design which did not influence British occultists. For him, the dancer is the Goddess of the World, the corporal soul of the universe, the Vestal Virgin of the hearth of life whose fire burns in every person. In her left hand, the dancer holds two wands with red and blue knobs at the end symbolizing the fire of life and the breath of air that constantly revivies the fire. Her hair flows behind her, reinforcing the concept of perpetual motion. The eagle is blue, the color of air.

The dancer’s body and legs form a triangle over a cross, the alchemical symbol for sulfur, which played an important role in Golden Dawn rituals. The position of her legs indicates she is the Hanged Man who has completed his spiritual journey. Occultists associated the four creatures in the corners of the card with the four Hebrew letters in God’s name, the four elements, seasons, fixed zodiac signs, and tarot suit symbols.

Interpreting the World Card

According to an 18th-century document, this card means “a long journey.” Cartomancers have extended this interpretation to include a change of location, travelling, and emigration. The entire world is available for exploration. There are no barriers to extending yourself and making the universe your home.

The card’s structure is an emblem of synthesis and integration. The central figure is the quintessence, the blend of the elements in the four corners. It signifies a breakthrough to a level of consciousness where there is no duality and no barriers to enlightenment. On a more mundane level, the card indicates the successful completion of an important project, or the end of a period of personal growth that culminates in a spiritual breakthrough. You have arrived and deserve to bask in the glow of your accomplishments.

Contemporary card interpretations tend to be psychological and describe the rewards of intense work on personal development: Self-actualization, psychic wholeness, an integrated personality, freedom from self-imposed limitations, and enjoying infinite possibilities.

Contemporary World Cards

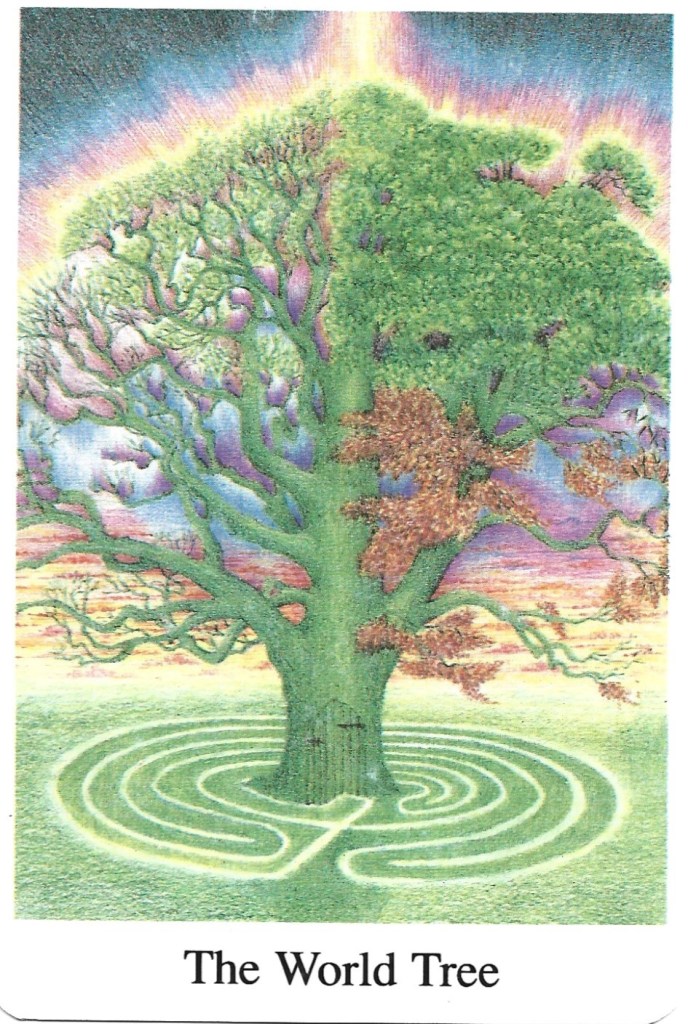

With its connection to ancient European mythology, the Greenwood tarot depicts the cosmos as the Norse World Tree, whose leaves and branches display all four seasons simultaneously. The labyrinth leads you to the barely visible door in the trunk. Once you enter the heart of the tree, your transformed consciousness allows you to travel in any direction, and to penetrate all dimensions of the cosmos.

The World card in the Songs for the Journey Home tarot is about feeling at home in the universe. The shell in the bottom foreground is our physical body which is made of stardust. Spirit grandmother lowers her braided hair to make a pathway to higher levels of the universe. Her outstretched arms span a bridge, inviting us to move as shamans do between dimensions. Physical and spiritual states are all the same—it’s all energy. There are no mental barriers to walking between worlds.

The Light Seer’s World dancer expresses the joy of being in that perfect moment when everything falls into place with grace and harmony, and you are on the brink of a breakthrough to a new level of consciousness. A large project, an era of your life, or a major journey has been successfully completed. Your inner and outer lives are congruent, and there are no more inner struggles. You are at a place in your life where you can just flow with the present moment.

See more cards and art at

https://www.tarotwheel.net/history/the%20individual%20trump%20cards/el%20mondo.html

Illustrations

Budapest Tarot, late 15th century. Recreated by Sullivan Hismans, Tarot Sheet Revival, 2017. Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

Cosmological Diagram. Les Echecs Amoureaux. Poem written c. 1375. Illustrated c. 1500. Collection of the Bibliothèque Nationale Française, Paris.

Triumph of Eternity. Pesellino, 1450. Collection of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Triumph of Eternity. Apollonia di Giovanni, 1442. Virtù d’Amore manuscript, 15th century.

New Jerusalem. Illuminated Manuscript. Collection of theMorgan Library, New York.

I Tarocchi Visconti Sforza. Milan c.1450. Reproduced by Il Meneghello, Milan, 2002. Collection of Pierpont Morgan Library, New York City.

Visconti Castle, Pavia. Contemporary photograph.

The Rosenwald Tarot, c. 1475. Re-created by Sullivan Hismans. Tarot Sheet Revival, 2017. Collection of National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Tarocco Bolognese Dalla Torre. 17th century. Reproduced by Marco, Benedetti, 2022. Collection of the Bibliothèque Nationale Française, Paris.

Codex Bruchsal, c. 1220. Collection of the Bedische Landesbibliotek, Karlsruhe, Germany.

Assumption of the Virgin. Bernardo Daddi, c. 1338. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum, New York City.

Tarot de Jacques Vieville. Paris, mid-17th century. Collection of the Bibliothèque Nationale Française.

Tarot de Marseille Jean Payen. Avignon, 1743. Facsimile by Marco Benedetti, 2023

Tarot de Marseille François Chosson, 1736. Restored by Yves Reynaud. Collection of the Historical Museum Blumenstein, Solothurn, Switzerland.

Oswald Wirth Tarot, 1887. Collection of the Bibliothèque Nationale Française, Paris.

The Centennial Waite Smith Tarot Deck. London, 1909. U.S. Games System, Inc., Stamford, CT, 2009.

Greenwood Tarot. Chesca Potter & Mark Ryan. 1996.

Songs for the Journey Home. Katherine Cook and Dwariko Von Summaruga. Self-Published, 1996, 2006.

The Light Seer’s Tarot. Chris-Anne. Hay House, Inc., 2019.

See the separate Bibliography for books that discuss all the trump cards.