La Papessa/La Papesse/The Popess/The High Priestess in Tarot

Certain Tarot cards like the Devil and Emperor are easy to interpret because devils and emperors are still part of our world. We have plenty of images in art and popular culture to give these cards a context. But some cards, like the Hanged Man and the Female Pope, are remnants of a lost medieval world with no contemporary examples to help us decipher their meaning. Without this historical perspective, we find ourselves projecting modern interpretations onto the cards with no reference to their historic roots.

La Papessa (her original Italian title) is a mysterious figure—a woman draped in ecclesiastical robes and wearing the pope’s triple crown. In the earliest Italian decks, she holds a book in one hand and the keys of Saint Peter, a bishop’s crook, or a staff in the other hand. La Papessa has been on a wild ride since the fifteenth century, going from a traditional allegory of the established Church, to a heretic, high priestess of an occult lodge and, most recently, a neo-pagan witch.

We moderns seem to need a subversive, even dangerous Popess. But is that how she was seen by the good Catholics who played Tarocchi with these cards in the 15th and 16th centuries? These early Tarocchi players were familiar with images of a female pope from the art of their time. Just as the Pope in the Tarot deck depicts a conventional, non-controversial religious figure, so the Popess was a conventional embodiment of the Church.

The Popess as an Allegory of the Church

The Popess may seem like an exotic figure to us, but a woman in papal regalia made many appearances in late-Medieval and Renaissance art. Allegories are usually rendered as a seated or standing woman holding symbolic objects, like the figure of Justice with her scales, or the Statue of Liberty. A woman with symbolic objects associated with the papacy did not seem at all strange or subversive until very recently, after the original meaning of the allegory had been forgotten. St. Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican, the very center of the Catholic Church, has a marble statue of a female Pope wearing the papal crown and holding a book and keys. She represents the Church itself and is obviously not a heretical figure. The medieval woodcut above shows a straightforward allegory of the Church used to illustrate Pope Joan. The curtain floating behind her became standard in the Tarot de Marseille pattern 150 years later.

The Popess as Pope Joan

If you’re casting about for a heretical figure to associate with this card, the legendary Pope Joan would be an obvious, but incorrect, choice.

The legend of Pope Joan first appears in Cologne, Germany in the 11th century. The story was repeated and embroidered by German monks throughout the high middle ages, and gained traction during the Protestant Reformation. The bare bones of the legend describes a 9th-century English woman who disguised herself as a man to pursue an education in the capital cities of Europe. After becoming known for his/her erudition and wisdom, (s)he was rewarded by being elected Pope. The Pope’s true identity was discovered while giving birth in the street during a religious procession. He/she died instantly and was buried on the spot.

It’s doubtful those early Tarocchi players would have seen Pope Joan in the Tarot card. Pope Joan is usually portrayed nursing a baby or with a baby tumbling out from under her robes. Most depictions are rather lurid and designed to create a shudder of revulsion. If the creator of the Tarot deck intended to portray Pope Joan, I think he would designed this card very differently.

The Visconti-Sforza Heretical Popess

When the Duke and Duchess of Milan commissioned a luxurious Trionfi deck shortly after assuming rulership of Milan in 1450, they may have inserted family history into many of the cards. Some historians believe La Papessa depicts a Visconti relative, Maifreda da Pirovano, who was burnt at the stake in 1300.

The story of the heretic Maifreda begins with Guglielma, a charismatic holy woman who appeared in Milan in the 1260s accompanied by a young son. Everyone assumed she was a widow, but nothing seems to have been known about her family or place of origin. After her death in 1282, her tomb at the Cistercian monastery of Chiaravalle near Milan became a pilgrimage site associated with miracles and visions. A cult quickly formed that was similar to many mainstream religious societies of the time.

Sister Maifreda and a priest, Andrea Saramita, both members of the Umiliati religious order, promoted the idea that Guglielma was the incarnation of a feminine, Christ-like, Holy Spirit. In 1300, several people associated with this cult, including Saramita and Maifreda, were burnt at the stake. A decade later, while investigating the head of the ruling Visconti family for heresy, Church authorities emphasized that the notorious heretic Maifreda was a Visconti cousin.

Gertrude Moakley was the first modern researcher to connect the Tarot card with the heretic Sister Maifreda. Moakley stated that the Visconti-Sforza Popess is dressed as a sister of the Umiliati order, therefore, she must be Maifreda. Moakley’s theory has one huge hole: The Visconti-Sforza Popess is dressed in the brown habit of the Franciscan Poor Clares with its distinctive knotted rope belt, not in the simple white habit of the Umiliati.

Why would a Poor Clare sister appear on a Visconti-Sforza tarocchi deck? A legend had been circulating around Lombardy since the early 1300s that Guglielma was actually Vilemina, the daughter of the king and queen of Bohemia. The real Vilemina had a younger sister who became Saint Agnes after establishing an order of Poor Clares in Prague with the help of Saint Clare of Assisi. Could the Visconti-Sforza card portray Guglielma’s supposed sister Agnes? There’s evidence that the Duchess of Milan was aware of the cult of Guglielma, which was still thriving in the vicinity of Milan in the 15th century. Perhaps this was the duchess’s way of referencing Guglielma in her deck while avoiding anything heretical.

The Early Italian and French Popess

How did the Popess appear in the earliest decks that weren’t commissioned by the aristocracy? Block-print decks from the 15th and 16th centuries show a generic, uncontroversial figure who is the counterpart to the Pope.

The earliest deck shown here is the Budapest Tarot from the last quarter of the 15th century. The Popess holds a bishop’s crook and the keys of Saint Peter. In the re-colored Rosenwald deck from about 1500, both Pope and Popess hold a very large key, while the Popess holds a book in her other hand. The French Popess from the mid-16th century is very similar to the earlier Italian cards. She holds a book and a very large key that’s nearly identical to the Pope’s key. In all these examples, as well as in the Tarot de Marseille decks of the next century, her crown has two levels rather than three, which is the Pope’s trademark.

When the Popess was Replaced

In spite of being conventional religious figures, the Pope and Popess were seen as problematic and were replaced with secular figures in some regions during the 18th century. In certain parts of France, Germany and Switzerland, Besançon decks substituted the Roman deities Jupiter and Juno for the Pope and Popess. This wasn’t done because the Catholic Church objected to religious figures on playing cards, as many people assume. These changes were made in heavily Protestant areas where people didn’t want to see Catholic imagery on their cards.

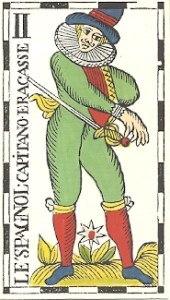

In Belgium and northern France, the Spanish Captain, a character from the Commedia dell’Arte, substituted for the Popess, while the Pope became Bacchus. The situation was a bit different in Bologna, where a political tempest created a new Bolognese-style Tarot deck. The Pope’s emissary in Bologna decreed that the Empress, Emperor, Pope and Popess were to be replaced by four Moors in all Tarocchi decks.

The Tarot de Marseille

c. 1660

1709

1840

By the late 17th century, the deck had settled into the Tarot de Marseille pattern. The French La Papesse was standardized into a seated woman wearing a heavy cloak and the papal tiara while holding an open book in her lap with both hands. A curtain with furled edges floats behind her head. The religious items displayed in earlier decks, the staff with a triple cross or bishop’s crook, and the keys of St. Peter have been eliminated. Only the papal triple crown remains. Above are examples of Tarot de Marseille cards from three different centuries showing how the imagery remained consistent over time.

Over the centuries, diverse cartomantic meanings have accumulated around this card. When the Popess is seen as a learned, high-status woman holding a book, the card may be interpreted as scholarly or scientific knowledge, mental clarity, or a woman who is a wise advisor. When the Popess is seen as embodying intuitive knowledge or spiritual understanding, this figure has a touch of the other-worldly, able to see behind the façade of consensual reality. She may be hiding something behind the curtain or under her veil, making her the guardian of esoteric knowledge, or a deceiver who withholds information. This card eventually acquired the lunar qualities of a goddess or sibyl. On the other hand, negative stereotypes of femininity are sometimes projected onto her. She can be unstable, emotional, superficial, or close-minded. In some cartomantic systems she represents a wife, mother or the female querant.

From Popess to High Priestess: French Occult Tarot

The Popess was called the High Priestess publicly for the first time in Antoine Court de Gébelin’s 1781 book of pseudo-anthropology Le Monde Primitif. De Gébelin firmly believed that the Tarot deck is a picture book preserving ancient Egypt’s most profound wisdom; therefore Christian imagery had to be a later distortion. He made it his mission to return the Tarot deck to its original Egyptian purity. De Gébelin renamed the Pope and Popess Le Grand-Prêtre and La Grande-Prêtresse (High Priest and High Priestess) and said they were a married couple, like the Egyptian religious leaders who bore those titles. His card description has the High Priestess wearing the horns of Isis, but his illustration of the card is nearly identical to the Tarot de Marseille pattern.

Someone who must have read de Gébelin created a more radical design, probably in the 1790s. The anonymous designer also called these cards Le Grand-Prêtre and La Grande-Prêtresse. Both figures are standing, dressed in elegant clothing, laurel wreaths on their heads and holding a palm branch. There is only one known copy of this deck in an American collection. It didn’t start a new tarot style, but it shows that as early as the 18th century, people were imagining a radically different Popess.

The greatest influence on the subsequent development of the Popess card was Eliphas Levi’s description in his 1856 book Transcendental Magic: “a woman is crowned with a tiara, wearing the horns of the Moon and Isis, her head enveloped in a mantle, the solar cross on her breast, and holding a book on her knees, which she conceals with her mantel.”

Following the French occultist tradition, Levi attributed the second letter of the Hebrew alphabet, Beth, to this card. This associates the card with the House of God, a sanctuary, and Gnosis, which leads to the idea that the High Priestess is sitting at the entrance to an inner sanctum. Levi also attributed the moon, the occult church, the mouth, speech, wife and mother to the card.

Oswald Wirth, an influential 19th-century French occultist, said of this card, “she is the priestess of mystery, Isis, the goddess of deep night and without her help the human spirit could not penetrate darkness”. Wirth redesigned his original 1887 deck in the early 20th century to make it conform to Levi’s original concept. The High Priestess’s throne is a carved sphinx. She rests the spine of the book on her knee and keeps a finger in the pages as if holding her place. Wirth interpreted the papal crown as two rows of precious gems representing Hermeticism and Gnosis, then he placed a crescent moon on top. He emphasized the dualities of the sun/moon, intellect/intuition and exoteric/esoteric knowledge with red and green pillars, silver and gold keys and a rather incongruous yin/yang symbol on the book. The curtain behind the La Papesse is attached to the pillars, reinforcing the idea that she is guarding the entrance to the inner sanctum for all except worthy initiates.

Wirth and his colleague Papus called this figure the Priestess of the Mysteries and the Goddess of the Night who possesses higher esoteric wisdom and secrets known to only a few. They emphasized lunar qualities of reflected light, passive receptivity, and knowing but keeping silent.

By the early 19th century, the Popess was drifting away from her medieval Christian context and was about to find a harbor in a strange new culture.

The Golden Dawn and Waite Smith Decks

French occultism jumped the English Channel in 1888 and was reborn in London as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. They called the second trump card the Priestess of the Silver Star and associated her with the Moon, Isis, and the ultimate expression of water. By association, she presides over things that fluctuate and are partly hidden. In the Golden Dawn system this card is the Hebrew letter Gimel—the camel that allows you to travel long distances because it stores water.

The most iconic High Priestess of the 20th century was created by two former members of the Golden Dawn, A. E. Waite and P. C. Smith. Their card follows Levi’s Egyptianized concept closely. The High Priestess wears the horns of Isis on her head representing three phases of the Moon. The equal-armed cross on her breast represents balanced dualities. Instead of a book, she holds a scroll labelled Torah to highlight its secret knowledge. The black and white pillars are inscribed with the letters for Boaz and Jachem, loosely representing an active/passive duality, which were supposedly inscribed on the pillars of the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. The High Priestess sits in front of a curtain embroidered with pomegranates and palms, guarding the entrance to the inner sanctum of the temple.

In his book, Pictorial Key to the Tarot, Waite couldn’t praise the High Priestess highly enough. He calls her the Secret Church, the Shekinah, the spiritual bride, supernatural mother, daughter of the stars. He says that in some respects this is the highest and holiest of the major arcana. Waite’s divinatory meanings for this card include: secrets, mystery, wisdom, silence, the unrevealed future, and a woman of interest in the reading.

Contemporary Cards

Once this card drifted from its original Christian context and became associated with all things lunar and mysterious, it was a short leap to seeing the High Priestess as a witch, sorceress, fortune teller or wise woman.

According to the creators of the Chrysalis Tarot, the youthful sorceress is a young Morgan La Fey. Dressed in boho gypsy style and accompanied by her raven familiar, she stirs a golden cauldron of transformation while magic mushrooms gather at her feet.

The Robin Wood High Priestess, as the lunar goddess’s representative on earth, is ready to lead her coven in a ritual under the full moon. The black and white trees in the background, and the book of knowledge and crystal ball of intuition illustrate the same dualities highlighted in esoteric cards. This priestess exhibits the mature qualities needed to lead a coven: practical experience, leadership skills and intuition.

The tavern fortune teller in the Pirate’s Tarot has mesmerized her client with her supernatural powers and her other attributes; although the crocodile on the wall doesn’t seem nearly as impressed. The tools of her trade, cards and grimoire, rest on the table with this down-to earth, working class sorceress.

Conclusion

Although she began as a symbol of conventional Christianity, the Popess has been associated with heretics and saints, and has been replaced by pagan figures at times. Her enigmatic appearance encouraged students of occultism to project their romanticized Egyptian fantasies onto her. By the time Tarot arrived in the English-speaking world, her Christian and Italian roots were forgotten. When tarot was incorporated into new-age, neo-pagan, and feminist subcultures in the mid-20th century, she morphed into a witch, sorceress, psychic or coven leader.

In spite of these radical changes, a continuous thread runs through her story. The Popess is an icon of deep spirituality that transcends dogma and formal religion. She is a paragon of intuitive understanding who sees beneath the surface of superficial distractions. She calls to us to slow down, enter our own inner sanctuary, and discover the wisdom waiting for us there.

see more cards and art at

http://tarotwheel.net/history/the%20individual%20trump%20cards/la%20papessa.html

Next Page: Pope

Read more about the Popess as a heretic

The Moors in Bolognese decks: https://tarot-heritage.com/from-trionfi-to-majorarcana/limperatore-lempereur-the-emperor-in-tarot/

The Spanish Captain in Tarot: https://tarot-heritage.com/2015/10/22/the-spanish-captain-in-the-vandenborre-deck/#more-1344

The story of Guglielma and Maifreda

- Illustrations

- Jacques Vievil Tarot c.1650. Restored and hand painted by Sullivan Hismans. Tarot Sheet Revival, 2019.

- Tarot of the Crone. Ellen Lorenzi-Prince. Arnell’s Art, 2017

- Allegory of the Church, Canon’s Chapel, St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome

- Woodcut from the book De claris selectisque mulierbus, Jacobus Philippus Forestus, Ferrara, 1497.

- Pope Joan Giving Birth. Woodcut from the book Boccaccio – Vornemmste, by Burgmair, c 1545. Cornell University Library collection.

- Visconti-Sforza Tarocchi, @1450, Pierpont Morgan Library, New York

- St Clare and the Poor Clares. Anastpaul.com.

- Budapest Tarot, late 15th century. Recreated by Sullivan Hismans, Tarot Sheet Revival, 2017. Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

- I Tarocchi Rosenwald, c. 1475. Re-created and colored by Marco Benedetti, 2019

- Catelin Geoffroy Tarot, mid 16th century. Collection of Museum fur Kunsthandwerk, Offenbach, Germany.

- Tarocco di Besançon, early 19th century, restored by Il Meneghello, 2000

- Spanish Captain. Tarot Flamand Vandenborre, Brussels, 1762. Restored by Pablo Robledo, Argentina, 2018.

- Tarocco Bolognese Al Mondo, 1725. Facsimile by Marco Benedetti, Rome, 2020. Collection of The British Museum.

- Jean Noblet Tarot c. 1660, Paris. Restored by Jean-Claude Flornoy, 2007. Collection of Bibliothèque Nationale Française, Paris

- Tarot Pierre Madenié, Dijon 1709. Restored by Yves Reynaud, 2016.

- François Gassman Tarot, Geneva, 1840. Restored by Yves Reynaud, 2020. Collection of the Swiss Game Museum.

- La Grande-Prêtresse. Kaplan, Stuart R. The Encyclopedia of Tarot Volume II, p. 337. Stamford: U.S. Games Systems, Inc, 1986.

- Oswald Wirth Tarot. Tchou Editeur. 1966.

- The Golden Dawn Tarot. Robert Wang and Israel Regardie. U.S. Games, Systems Inc., Stamford, CT, 1977.

- The Rider Tarot Deck, A. E. Waite and P.C. Smith, 1909, U.S. Games Systems, 1971

- Chrysalis Tarot. Toney Brooks and Holly Sierra, U.S. Games Systems, 2016

- The Robin Wood Tarot. Robin Wood. Llewellyn Publications, 1991

- Tarot of the Pirates. Lo Scarabeo, 2008.

References

Gebelin, Book VIII, Tarot section. Evalyne’s Garden Gate, 2016.

Greer, Mary K. https://marykgreer.com/2009/11/07/papess-maifreda-visconti-of-the-guglielmites%e2%80%94new-evidence/

Hall, Evalyne K. Du Jeu des Tarots et Recherches sur les Tarot. Translation of Antoine Court de Hurst, Michael J. http://pre-gebelin.blogspot.com/2013/04/the-catholic-church-in-rome.html

Moakley, Gertrude. The Tarot Cards Painted by Bonifacio Bembo. The New York Public Library, 1966. Pages 72-73.